widowland

widowland is a place of hope and loss. While it is a reflection on a history of lost husbands, it also celebrates the strength and endurance of complex relationships. Far more than the story of mortality and absence, widowland shows, through emptiness, repetition and solitude, a life of fullness, rarity and partnership. The roots of this story are in my own family. I am from a family of widows. My “nana” lost her husband in 1965. She lived without him, but with him for another 35 years. My mother lost her husband in 1999. She has lived without him, but with him for another 10 years, so far. My grandma’s death preceded her husband, but I think perhaps she lost him in 1987 when he had a stroke, leaving him without speech or facility of his right side. She lived without him, but with him in for another 6 years. I admire these women. I admire their commitment to the men who were husbands, friends, and partners all their lives. This commitment was not lost with death, only changed. While I’ve deeply considered these relationships in the process of making this installation, this is not just a biography or a portrait. These relationships are inspiration for issues more central and universal. With this exhibition, I hope the viewer to consider the qualities of loss, love, sentiment and strength.

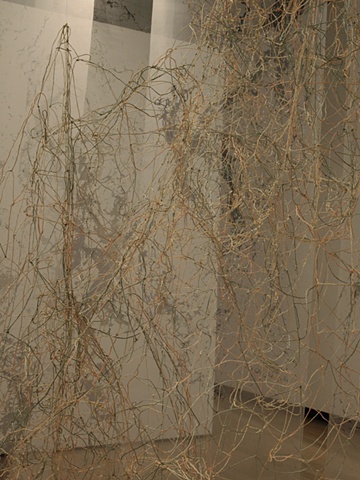

Centered in the middle of the exhibition are three large, hand-knotted nets. The net is an object full of its own connotations and also analogous to objects such as the web and the cocoon. The net is a trap and also a source of protection. The web is both a home and a final resting place. The spider of the web is a predator but also often a mother and a weaver. Drawing on the legacy of Penelope weaving and then tearing out her stitches, awaiting the return of Odysseus, each knot was made carefully, one at a time, then formed and re-knotted together to create the voluminous, empty cocoons. The cocoon represents a state of transition, formed as an encasement for metamorphosis, when a being enters at one stage of life and emerges from it at another. Knowing the potential for loss and entanglement, we enter into these nets/webs/cocoons, we become them, they are bodies, containers of themselves, their own losses and dreams.

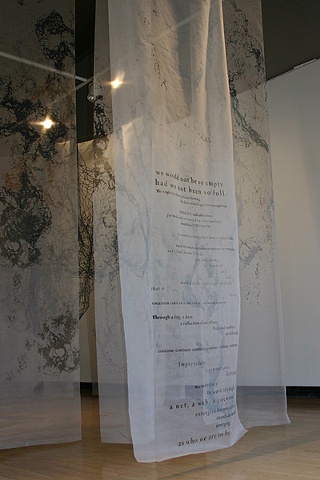

Surrounding the central nets are sheer panels with the impression of the nets repeated one atop another. These forms are not the full/empty shells that are the net/web/cocoon, but flattened, and dulled versions, a shadow of the bodies, forming a collection of detritus. These shadows protect the fragile bodies but are also an obstacle for the viewer. Translucent, you can see that there is a way to the other side, but the way is unclear. Once through the barriers, the viewer is alone with the bodies/nets/webs/cocoons, sharing their space, their journey, their loss, their joy.

Repetition is essential to these pieces. Repetition, through the repeatable matrix, from which one can become many, is the essence of printmaking. These multiples are often spread apart from one another, utilizing the multiple in isolation, in dissemination. I value the multiple for its potential to become an accumulation, a prompt to become meditation, and for its quantity and scale. For only by comparing many, can we see and recognize what is rare. A multitude of objects, like the many fragments of objects of "Cornelia Parker’s Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View" (1991), prompt the viewer to look for and compare the subtle differences between the

objects, making the story more rich, and creating depth of space and narrative. In repetition,

each knot follows the same form, but each holds a slightly different tension. In repetition, the stories of our mothers become our stories. In repetition, heartache is felt again and again, and transforms from sharp pain to a soft throb. In repetition, we can become disoriented, but emerge with order. In repetition, sentiment and strength become one.

The combination of strength and sentiment are at the heart of this show. I find often that places where contradiction is present, I find inherent harmony. Seemingly disparate ideas, thoughts, objects connect themselves to create so simple and subtle a truth that is undeniable; it is astounding; it is heartbreaking. In a space filled with many repeated objects, there is a sense of loneliness, emptiness, and sorrow; however, we are only able to recognize these absences by acknowledging the pieces that are missing. Commitment, partnership, abundance of love and life so fill these bodies, that mortality cannot obscure it. Just as we see the empty bed, posted on billboards, in Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s work Untitled (1991), and contemplate both the emptiness and loss of that bed, we also consider the couple that once laid their heads there. Absence implies presence. We would not be so empty, had we not been so full.